Melasma is a complex and persistent skin condition that causes dark, patchy discoloration, often on the face. While it’s most common in women with medium to darker skin tones, melasma can affect anyone. Unlike other forms of hyperpigmentation, melasma affects not just the surface of the skin but also the deeper layers, making it notoriously difficult to treat and prone to recurrence. Its chronic nature means managing melasma requires patience, consistency, and a tailored approach. I want to dive deeper into the science of melasma, its connection to sun damage, and the effective treatments available today.

What Is Melasma?

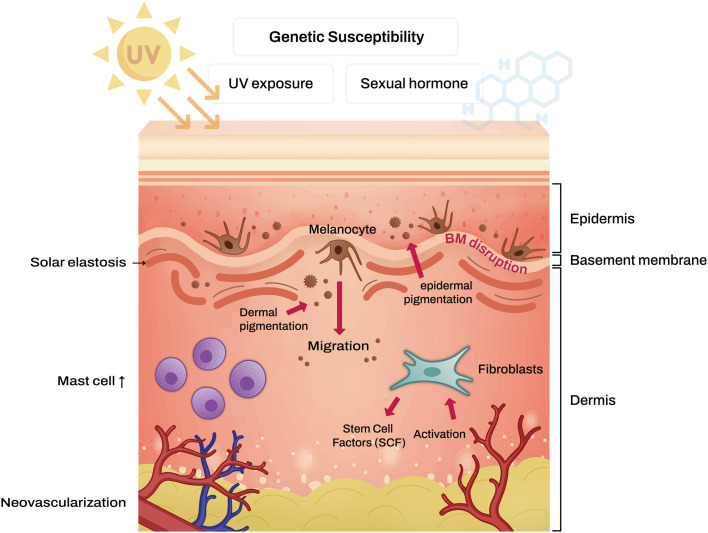

Melasma is an acquired form of hyperpigmentation characterized by brown to gray-brown patches on sun-exposed areas, particularly the face. It often appears symmetrically on the cheeks, forehead, upper lip, nose, and chin. Its exact cause isn’t fully understood, but factors like UV exposure, hormonal changes (e.g., during pregnancy or while using oral contraceptives), and genetics are key contributors.

Why Is Melasma So Difficult to Treat?

One of the biggest challenges with melasma is its chronic nature and tendency to recur. Here’s why:

- Persistent & Recurring: Melasma tends to come back even after treatment. It’s not a “one and done” condition; instead, it requires continuous care to keep it under control.

- Triggered by Multiple Factors: Melasma is often influenced by UV exposure, hormones, genetics, and even stress. These factors can make it difficult to manage and contribute to its recurrence.

- Goes Deeper Than the Surface: Melasma affects not just the top layer of skin but also the deeper layers, which is why treatments targeting only the surface may fall short in providing lasting results.

- Similar to Aging Skin: Melasma shares features with skin aging, like damage to collagen and elastin, which complicates treatment and makes it harder to maintain clear skin over time.

Dermal melasma: A the appearance of melasma under normal light, B the appearance of melasma under Wood lamb, no enhancement is seen. C, D dermoscopic examination; Blue rectangles: gray pigmentation superimposed upon irregular, faint brown pseudonetwork, red vertical arrows: perifollicular hyperpigmentation, blue arrowheads: increased vascularity and telengiectasia, green transverse arrows: light brown clod, blue circle: annular-arcuate structures, gray rhombi: irregular brown pseudonetwork. Source

Melasma and Sun Damage

Melasma shares similarities with photoaging, which is the premature aging of the skin caused by prolonged exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation. Both conditions have visible changes like dark spots, uneven skin tone, and structural damage that go beyond the surface. These shared characteristics make melasma particularly challenging to treat, as many conventional treatments focus solely on the outermost layers of the skin while neglecting the deeper damage that contributes to its persistence.

One key connection between melasma and photoaging is the impact of UV damage. In both conditions, sun exposure accelerates the production of melanin, leading to hyperpigmented spots and patches. UV radiation doesn’t just affect the surface, it penetrates deeper into the skin, causing the breakdown of collagen and elastin, which are vital for maintaining the skin’s structure and elasticity. This damage creates a weakened skin barrier, making melasma harder to treat and more likely to recur, especially without strict sun protection.

Hormonal influences also tie melasma to photoaging. Just as hormonal changes during menopause can exacerbate signs of aging, fluctuations in hormones—such as those experienced during pregnancy or from contraceptive use—can trigger or worsen melasma. These hormonal shifts stimulate melanocytes (pigment-producing cells), increasing melanin production and contributing to the formation of the characteristic dark patches associated with the condition.

Additionally, melasma causes deeper “photoaging-like” changes in the dermis, the skin's support layer. Chronic UV exposure and inflammation disrupt the basement membrane, a critical structure that separates the epidermis from the dermis. This disruption allows pigment and melanocytes to drop into the dermis, making the pigmentation more resistant to treatments like topical creams and chemical peels that primarily target the surface. The breakdown of collagen, increased vascularization, and inflammation in the dermis further contribute to melasma’s stubborn nature, highlighting the need for a comprehensive treatment approach that addresses both the surface and deeper layers of the skin.

Why Treatments Alone Often Aren’t Enough

Treating melasma is rarely straightforward, as it involves more than just addressing pigmentation on the surface of the skin. While conventional treatments like topical creams, chemical peels, and even certain lasers can lighten the dark patches, they often fall short of providing long-term results. These surface-level treatments target the epidermis, the outermost layer of skin, but melasma often extends deeper, affecting the dermis. The condition's chronic and multifaceted nature means that addressing only the surface fails to tackle the root causes, such as structural damage and inflammation in deeper layers.

One of the biggest obstacles to successful melasma treatment is recurring UV damage. Even after achieving initial improvement, exposure to ultraviolet (UV) rays can quickly trigger melasma’s return. UV radiation not only stimulates melanocytes (pigment-producing cells) to produce more melanin but also exacerbates underlying inflammation and structural breakdown. Without strict and consistent sun protection—such as broad-spectrum sunscreen, protective clothing, and avoidance of peak sunlight hours—UV damage continues to fuel the condition, undoing progress made with treatments.

The chronic nature of melasma also plays a significant role in its resistance to treatments. Melasma is inherently stubborn due to underlying skin damage, such as a disrupted basement membrane and collagen breakdown in the dermis. These factors make it prone to recurrence even after successful treatment. Long-term maintenance, including daily sun protection, lifestyle adjustments, and periodic use of lightening agents or in-office procedures, is essential to managing melasma. Without a comprehensive, ongoing approach, melasma can quickly resurface, leaving patients feeling frustrated. Addressing both the surface symptoms and the deeper structural issues is key to achieving lasting improvement.

Beyond the Surface: Understanding Melasma and the Skin’s Structure

Melasma isn’t just a surface-level skin issue—it goes much deeper, affecting the intricate layers and structures beneath the surface. This is why it’s so persistent and difficult to treat with surface-only methods like creams or chemical peels. To effectively manage melasma, we need to address the condition’s root causes, which involve overactive pigment production, structural damage in the dermis, and even changes in blood flow.

At the heart of melasma are overactive melanocytes, the cells responsible for producing melanin. These cells are triggered by factors like UV exposure, hormonal fluctuations, and inflammation, leading to the visible dark patches on the skin. However, melasma doesn’t stop there. The condition often involves damage to the deeper support structures of the skin, including collagen and elastin. These proteins provide strength and elasticity to the skin, but in melasma, UV-induced damage and chronic inflammation break them down. This structural degradation weakens the skin’s foundation, making the pigmentation more resistant to treatment and more likely to recur.

Another factor that complicates melasma is increased blood flow in the affected areas. Research shows that melasma often involves the formation of new blood vessels, a process known as angiogenesis. These vessels release growth factors that can stimulate melanocytes further, worsening pigmentation. This vascular component explains why treatments targeting only pigmentation may not be enough—addressing blood vessel growth and inflammation in the dermis is also crucial. A truly effective melasma treatment plan requires a comprehensive approach that tackles these deeper layers, restoring the skin’s structure while reducing pigmentation and inflammation.

Treatment Approaches for Melasma

Effectively managing melasma requires a combination of treatments that address both the surface pigmentation and deeper structural changes in the skin. This multi-layered approach targets melasma’s complexity and helps reduce the likelihood of recurrence.

Topical Agents

Topical treatments are often the first step and help improve pigmentation on the skin’s surface:

- Hydroquinone: A gold-standard ingredient that reduces melanin production and lightens dark patches.

- Retinoids: Promote skin cell turnover, allowing pigmented cells to be replaced with healthier ones.

- Azelaic Acid & Kojic Acid: Natural alternatives that reduce pigmentation and inflammation with less irritation.

New studies are emerging in regards to topical proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and Methimazole, an oral anti-thyroid medication commonly used to treat hyperthyroidism. As they may also inhibit melanogenesis, while methimazole blocks melanin synthesis as a potent peroxidase inhibitor, presenting a promising treatment for melasma.

Oral Medications

For stubborn or recurring cases, oral medications work on deeper factors contributing to melasma:

- Tranexamic Acid: Reduces inflammation and blood vessel formation, targeting the vascular component of melasma.

- Polypodium leucotomos (PL), a tropical fern native to Central and South America, is recognized for its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and photoprotective properties. It works by neutralizing reactive oxygen species (ROS) and preventing lipid peroxidation. While oral PL extract (PLE) has been explored as a potential treatment for melasma, the results have been inconsistent and inconclusive.

-

Best For: Patients with frequent flare-ups or pigmentation that doesn’t respond fully to topical treatments.

In-office procedures provide additional support by targeting both the surface and deeper layers of the skin. Chemical peels, such as glycolic acid peels, exfoliate the outermost layer of skin, removing pigmented cells and revealing a brighter complexion. For deeper pigmentation, laser therapy can break up pigment deposits while stimulating collagen production to improve skin texture and support. However, these treatments must be carefully tailored to avoid irritation or worsening pigmentation, especially in patients with darker skin tones.

Together, these treatments offer a comprehensive approach to melasma management. Combining them allows for targeted results, addressing both the visible symptoms and the deeper causes of melasma, while reducing the chances of recurrence. Regular follow-up and maintenance are key to sustaining these improvements.

Why Melasma Needs Consistent Maintenance

Melasma is a chronic condition, which means that even after achieving noticeable improvement, ongoing care is essential to prevent it from returning. Consistent maintenance ensures that progress is sustained and flare-ups are minimized.

Key Maintenance Practices

-

Daily Sunscreen:

- Use a broad-spectrum SPF with iron oxide to block both UV and visible light, which can worsen melasma.

- Reapply every 2-3 hours, especially if you’re outdoors or sweating.

-

Avoiding Triggers:

- Minimize exposure to UV rays, stress, and heat, as these can exacerbate melasma.

- Wear protective clothing and seek shade during peak sunlight hours.

-

Long-Term Topical Use:

- Incorporate gentle skin-lightening agents like azelaic acid, niacinamide, or low-dose hydroquinone to maintain results.

- Rotate or adjust treatments as needed under guidance.

Patience and Persistence Pay Off

Managing melasma is a long-term journey, but with the right approach, significant and lasting results are within reach. Improvement doesn’t happen overnight—it takes time, often months, to see the progress you’re aiming for. Setting realistic expectations is key, and so is celebrating every small step forward along the way. Melasma is a condition that requires commitment, but the results are worth it when you stay consistent with your care.

Partnering with me as an experienced facialist can make all the difference. Your skin is unique, and your treatment plan should be too. Together, we can create a customized strategy tailored to your skin’s needs, addressing melasma at every level—from surface pigmentation to the deeper layers that contribute to its persistence. As your skin changes, your plan can adapt to keep you on track for lasting improvement.

Consistency is the secret to success. From daily sunscreen to personalized treatments, sticking to your routine is what helps control melasma and prevent it from coming back. Ready to take the next step? Request to work with me today, and let’s build a plan that works for your skin and lifestyle.

References

- Sarkar R, Bansal A, Ailawadi P. Future therapies in melasma: what lies ahead? Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2020;86:8–17.

- Kwon SH, Hwang YJ, Lee SK, Park KC. Heterogeneous pathology of melasma and its clinical implications. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:824.

- Handel AC, Lima PB, Tonolli VM, Miot LD, Miot HA. Risk factors for facial melasma in women: a case-control study. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:588–594.

- Rajanala S, Maymone MB, Vashi NA. Melasma pathogenesis: a review of the latest research, pathological findings, and investigational therapies. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25:25.

- Kang HY, Hwang JS, Lee JY, Ahn JH, Kim JY, Lee ES, et al. The dermal stem cell factor and c-kit are overexpressed in melasma. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:1094–1099.

- Kim M, Kim SM, Kwon S, Park TJ, Kang HY. Senescent fibroblasts in melasma pathophysiology. Exp Dermatol. 2019;28:719–722.

- Kang HY, Suzuki I, Lee DJ, Ha J, Reiniche P, Aubert J, et al. Transcriptional profiling shows altered expression of Wnt pathway- and lipid metabolism-related genes as well as melanogenesis-related genes in melasma. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:1692–1700.

- Kim JY, Lee TR, Lee AY. Reduced WIF-1 expression stimulates skin hyperpigmentation in patients with melasma. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:191–200.

- Kim M, Han JH, Kim JH, Park TJ, Kang HY. Secreted frizzled-related protein 2 (sFRP2) functions as a melanogenic stimulator; the role of sFRP2 in UV-induced hyperpigmentary disorders. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136:236–244.

- Kim JY, Shin JY, Kim MR, Hann SK, Oh SH. siRNA-mediated knock-down of COX-2 in melanocytes suppresses melanogenesis. Exp Dermatol. 2012;21:420–425.

- Lee DJ, Park KC, Ortonne JP, Kang HY. Pendulous melanocytes: a characteristic feature of melasma and how it may occur. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:684–686.

- Torres-Álvarez B, Mesa-Garza IG, Castanedo-Cázares JP, Fuentes-Ahumada C, Oros-Ovalle C, Navarrete-Solis J, et al. Histochemical and immunohistochemical study in melasma: evidence of damage in the basal membrane. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:291–295.

- Na JI, Choi SY, Yang SH, Choi HR, Kang HY, Park KC. Effect of tranexamic acid on melasma: a clinical trial with histological evaluation. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1035–1039.

- Siiskonen H, Smorodchenko A, Krause K, Maurer M. Ultraviolet radiation and skin mast cells: Effects, mechanisms and relevance for skin diseases. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27:3–8.

- Lee HJ, Park MK, Lee EJ, Kim YL, Kim HJ, Kang JH, et al. Histamine receptor 2-mediated growth-differentiation factor-15 expression is involved in histamine-induced melanogenesis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2012;44:2124–2128.

- Yoshida M, Takahashi Y, Inoue S. Histamine induces melanogenesis and morphologic changes by protein kinase A activation via H2 receptors in human normal melanocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;114:334–342.

- Iddamalgoda A, Le QT, Ito K, Tanaka K, Kojima H, Kido H. Mast cell tryptase and photoaging: possible involvement in the degradation of extracellular matrix and basement membrane proteins. Arch Dermatol Res. 2008;300(Suppl 1):S69–S76.

- Coussens LM, Raymond WW, Bergers G, Laig-Webster M, Behrendtsen O, Werb Z, et al. Inflammatory mast cells up-regulate angiogenesis during squamous epithelial carcinogenesis. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1382–1397.

- Kang WH, Yoon KH, Lee ES, Kim J, Lee KB, Yim H, et al. Melasma: histopathological characteristics in 56 Korean patients. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:228–237.

- Parkinson LG, Toro A, Zhao H, Brown K, Tebbutt SJ, Granville DJ. Granzyme B mediates both direct and indirect cleavage of extracellular matrix in skin after chronic low-dose ultraviolet light irradiation. Aging Cell. 2015;14:67–77.